Sunak promises shorter NHS waiting times moments after Brianna Ghey trans jibe – but in Manchester it’s trans people who have to wait longest

Sunak’s promises came moments after making a transphobic comment while Brianna Ghey’s mother attended the Commons during PMQs.

Rishi Sunak attracted widespread condemnation for his refusal to apologise after making a transphobic comment in the House of Commons on Wednesday (7 February) – on the same day the mother of murdered trans teenager Brianna Ghey attended Parliament.

He also admitted his failure to bring down NHS waiting lists during his time as Prime Minister and promised to commit to shortening waiting times for those worst affected.

However, for many members of Manchester’s transgender community, the Prime Minister’s words ring particularly hollow as figures show that those pursuing gender-affirming care are waiting years for an appointment.

What does gender-affirming care on the NHS look like?

Unlike many countries, in the UK being transgender is classified as a medical condition, known as ‘gender incongruence’. Only those with a diagnosis of gender incongruence can medically transition in the UK.

Transgender adults seeking gender-affirming care are encouraged to speak to their GP, who will refer them to a gender identity clinic (GIC), where they will be assessed by a psychiatrist to check if they meet the criteria for gender incongruence.

Those who meet the criteria are then referred to an endocrinologist for blood tests, who will then prescribe hormone replacement therapy if the results are clear.

However, the current system has attracted widespread criticism from the trans community, with one survey by community organisation TransActual revealing that 98% of respondents felt that NHS transition-related care was ‘inadequate’ in 2021.

Common criticisms of the current system include the lack of an informed consent model, lack of regional services, and long waiting lists, with some patients waiting up to seven years for an initial assessment.

‘It just wasn’t possible’

For many in Manchester, the situation can be particularly difficult.

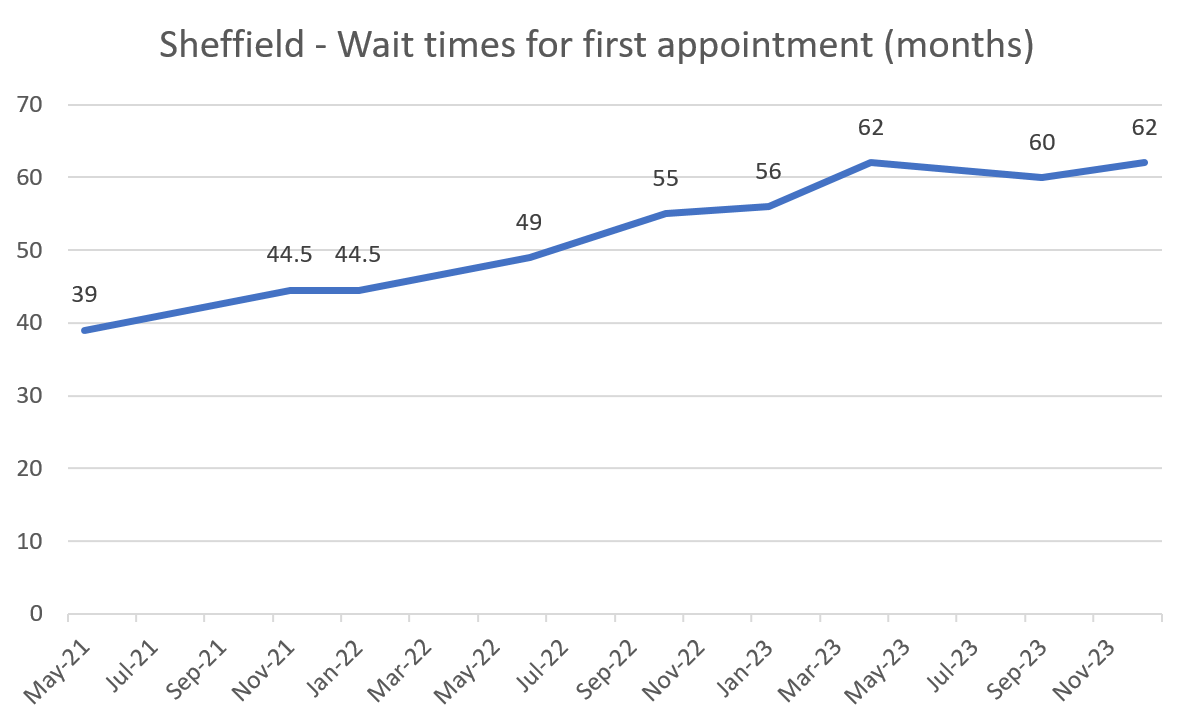

The nearest GIC – in Sheffield – has a current waiting list of over five years for an initial assessment. Manchester’s own GIC, Indigo, is a pilot scheme with a two-year waiting list, but only accepts referrals from those already on waiting lists for other clinics.

Alex, 20, is a transgender man who grew up in Manchester, who has since moved to Bangor to study psychology. He has been out as trans for three years, and been on testosterone for six months, describing himself as ‘lucky’.

Speaking to NQ, he said: “I did try to go the NHS route when I came out. I was referred to Leeds, which was the closest one at the time, and the waiting list back then was about six years.

“I didn’t end up staying, because I went private, and you know. The way my mental health was at the time, I just couldn’t wait that long. Waiting six years for an assessment, just for someone to tell you whether you’re trans enough or not, and then obviously having to wait for another appointment – it just wasn’t possible.”

Alex turned toward the private sector for treatment, an option he feels fortunate to have been able to pursue given the costs involved. After his own diagnosis, he was referred to a hormone clinic in London.

“It can get so expensive, I’m lucky to have had family members who were, you know, willing to support me. And I did work out an estimate of how much roughly I’d need and worked for it and saved up.

“My hormone clinic do charge a subscription fee to stay within the service, and then I pay for my prescription. Privately, obviously. And sometimes when you pay, sometimes it’s a reasonable amount, and sometimes it gets really, really expensive. When I first got my prescription, I got three bottles for about £45, and then the next time, I got two bottles for £85.

“The private appointment was really expensive, and then from there, having to go down to London if I need to, it’s a lot. I’m really lucky to have family who live outside of London so if I need to go, I can just stay with them, and then not have to pay for a hotel as well as, you know, everything else.”

‘A community where everyone has a role’

Georgia Williams, 21, has been the chair of Man Met’s LGBTQ+ society since September, though they had been on the committee the year before.

They emphasise the importance of community when dealing with hardship, particularly on a local scale.

Georgia said: “I think Manchester has a lot to offer, it can just be difficult to find your home within the community. I’ve found a lot of love and acceptance within the local Manchester drag scene – I’m part of a Drag King collective, and having a space that encourages challenging the boundaries and binaries of mainstream society has been so healing for me.

“I think these spaces are absolutely essential. In an ideal world they wouldn’t be necessary, as LGBTQ+ people would be accepted and celebrated everywhere, but as the government is clearly showing, this isn’t the case.

“I think for the people within the community who think we should be grateful for what we have, I’d ask them to reflect on their position – how close are they to the experiences of the most vulnerable within our community?

“To those outside the community, I’d have to ask why they think the blatant marginalisation of LGBTQ+ people is acceptable to them, why we should be grateful for the dehumanisation we receive.”

Talking about their responsibility as the chair of the society, they added: “I’ve definitely had to come to terms with the fact that I’m only one person with a set amount of resources and time. I can only do as much as my capabilities allow – and that’s okay.

“I think actions speak louder than words – or rather, words should be accompanied with actions. I hope what I’m doing is offering some form of comfort or space [to those feeling most hopeless in the community] in which they can just exist, and that the space will be available for them as long as I can offer it.

“Being a part of the community is exactly that – a community where everyone has a role, and it doesn’t just have to be me.”