Standing on the shoulders of giants: A guide through Manchester’s forgotten radical journalists

- Pete Murray guides us through the role the radical press played as part of the 19th Century Chartist movement to extend the voting franchise and to make the UK Parliament more representative

Both journalism and history are often at their most compelling for us when they touch our lives personally.

So, amid bone-dry coverage of interest rates or inflation rates, most of us find our eyes jumping to the section about how any change will affect what’s laughably still sometimes described as our disposable income; or when harrowing footage from the Syrian war makes us hold our children a little closer.

It can be the same with old stories of our trade, or the inspiring lives and work of some of the early giants of our profession upon whose shoulders we stand.

One of those giants is Barrhead-born Helen MacFarlane, the reporter, commentator, translator and activist who became a leading figure in the Chartist movement during the mid-19th century.

After her fiery years of engagement in the working class democratic movement around Manchester and Lancashire in the 1840s and early 1850s – writing for the Red Republican and completing the first translation into English of The Communist Manifesto – she ‘retired’ into the relative obscurity of marriage to the local vicar in a small village near Nantwich, in Cheshire, where she died in 1860 at the age of 41.

Before I began work in Manchester earlier this year, I’d never heard of Helen Macfarlane, although I had heard of the Chartists – for the first time, many years ago in secondary school history classes. Back then, we were mostly taught about how the Charter had been a challenge to the Whig and Tory orthodoxy of the day (cue a chorus of adolescent yawns!).

I do remember passing references to the Northern Star newspaper, and its editor Feargus O’Connor.

However, I don’t remember hearing quite so much in the classroom about how Chartism was a working class movement for democracy that engaged hundreds of thousands of people from Scotland’s Central Belt, through Cumbria and Lancashire, across the south and east of England, right to the gates of Westminster and the mass rallies, such as in Kennington Park – which many years later became the gathering point for one of the feeder marches on the day of the great 1990 Anti-Poll Tax demonstration.

Nor was there that much either in school about William Cuffay, the black activist and organiser who was convicted of involvement in a bombing plot (mostly on the strength of what even the trial judge thought was questionable testimony from a police supergrass) and transported to the prison colonies of Tasmania.

Nor even about my near-namesake, Peter Murray McDouall, another of the Chartist organisers – by all accounts one of the movement’s most passionate and eloquent public speakers – who also made numerous appearances in court for his pains.

But arriving in Manchester and being asked to devise some lectures about the history of journalism, the Northern Star seemed like a good place to start.

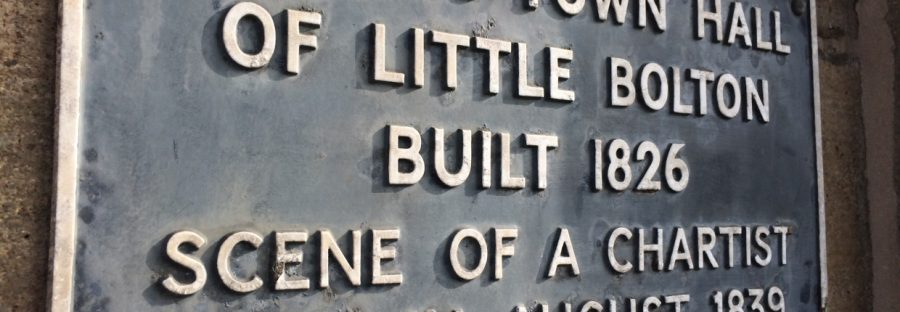

So, the last couple of months have taken me to Helen MacFarlane’s graveside, to the location a couple of miles from where I now live of a Chartist “riot” outside the old Town Hall of Little Bolton (memorial plaque, above), and to the commanding, bleak, windswept summit of Blackstone Edge, where thirty thousand people gathered for a Chartist rally on the hillside in 1846.

It has also taken me – and some colleagues, along with several dozen of our new journalism students at Manchester Metropolitan University – to the People's History Museum, which has one of the most exhaustive archives in the country of Chartist newspapers, pamphlets, letters and printed flyers – as well as what is probably the first ever photograph of a political rally ever taken in the UK, that historic gathering of up to 25,000 people in Kennington Park.

You can watch our interview with PHM archivist Darren Treadwell here:

Back in those dusty history classes I don’t remember we were ever taught that much about the pioneering, campaigning journalism that accompanied the movement and grew out of the social and economic upheavals, poverty and suffering of those years – “Hunger and hatred: these were the forces that made Chartism a mass movement of the British working class,” writes GDH Cole (Chartist Portraits. Published by Macmillan, 1941).

However, many of those journalists – Helen MacFarlane, James Bronterre O’Brien, Anne Knight, or Henry Hetherington of the Poor Man’s Guardian – would all surely recognise how their passion and commitment lives on today in the work of some of our best writers and social commentators: from Paul Mason to Laurie Penny and Owen Jones, from Common Space or the Bristol Cable, to Article 19 and NovaraMedia.

This is history that touches us today, informs us, and enriches us all.