The day three future presidents visited Chorlton

One morning in autumn, three future presidents, a Communist boxer, and a feminist descended on the Chorlton-on-Medlock Town Hall. In the October of 1945, 87 delegates from more than 20 nations gathered before an audience of hundreds. While Britain’s soldiers recovered in a newly-freed Europe, veterans from the wider Empire had just returned home to nations still engulfed by imperial violence.

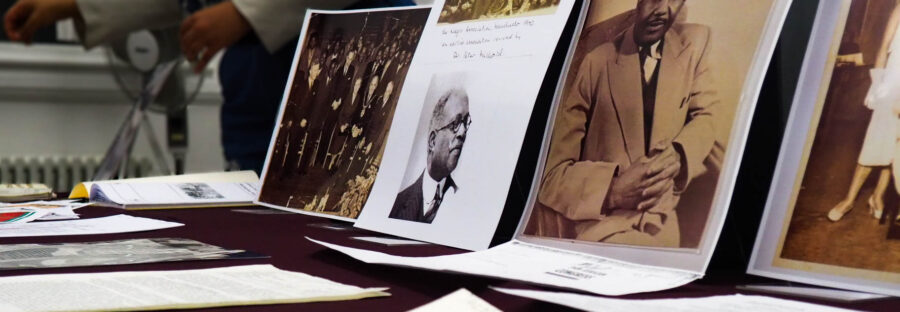

Decades later, organisations across Manchester are looking back on the 80th anniversary of the Fifth Pan-African Congress. Held between 15 and 21 October, 1945 in what is now Man Met’s Grosvenor East building, the week-long series of meetings encouraged people of African descent to unite against racial injustice, inequality and colonialism in Africa.

With the Congress now being memorialised across a series of talks, exhibitions, and a biting Royal Exchange production, thousands are now looking back on the week said by many to have cracked the ice over African independence.

‘How long is this vicious discrimination to continue?’

During the First World War, Britain had extended an open hand to the people of their colonies, promising movement towards self-government if they fought for the Allies. The fist was quickly tightened at the final hour, however, and with similar promises made – and backtracked on – by Churchill in 1941, simmering demands for decolonisation and racial equality would begin to boil over across the Empire.

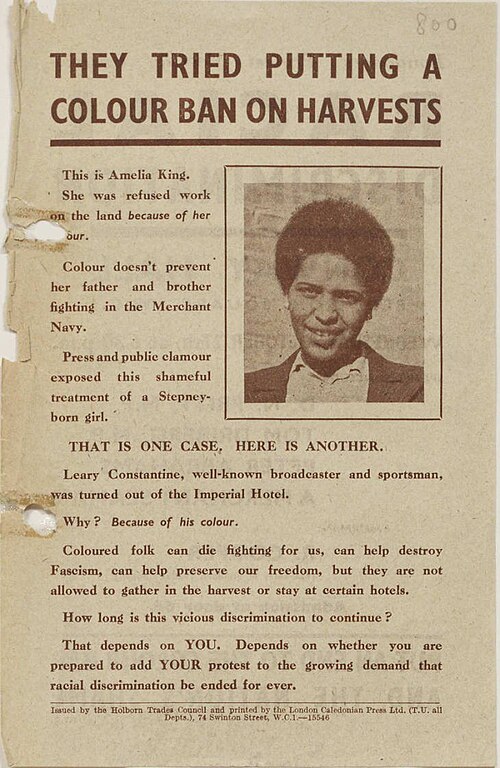

Meanwhile in the UK, competition for labour and jobs after the Second World War would only widen gaps between white and non-white veterans. Against the backdrop of an employment colour bar; Black youth unemployment; racial discrimination; and the sly import of informal segregation from American troops, the delegates gathered at the town hall on the 15th October for the first session of the Congress.

Attendees included Hastings Banda of Malawi, Jomo Kenyatta of Kenya, and Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana, who would all go on to be the first presidents of their free countries. Also with them were the feminist and human rights campaigner Amy Ashwood-Garvey, and Les Johnson, a champion boxer and Communist from Moss Side.

The group would come to the week-long series of meetings demanding freedom from colonialism – and, according to future-Ghanaian president Nkrumah, would leave “knowing definitely where we were going”.

‘There was no question about where this congress should be held’

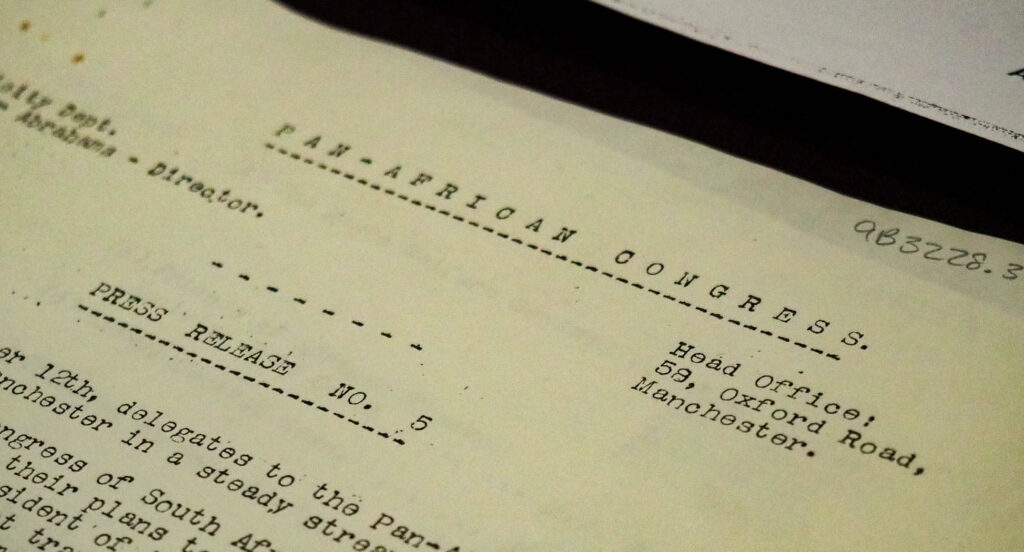

The decision to host the Fifth Pan-African Congress in Manchester was due in no small part to Manchester businessman and activist T. Ras Makonnen.

Born in British Guiana (now Guyana), Makonnen would move to Manchester following the Second World War and go on to open several restaurants, hotels, a nightclub, and bookshop on Oxford Road. Looking back on the event, Makonnen would later write: “There was no question about where this congress should be held.

“We had all the convenience in Manchester. Fortunately for my people, I had succeeded in establishing myself as a businessman in this place.

“I knew the Lord Mayor, and also Harold Laski’s brother, who held an important position in the Labour Party. I was a member of the party myself, and had connections with Bolt, who was the local secretary.

“All of this made it relatively easy to get halls booked for the Congress and simplify the question of hotel accommodation.”

Makonnen would become treasurer for the Congress and is named on a plaque commemorating the event on the wall of Grosvenor East. Also named on the plaque is Amy Ashwood-Garvey, described by local historian Dr Parise Carmichael Murphy as “a real leader in her own right”.

“Born in Jamaica, she co-founded the Universal Improvement Negro Association,” she said in a talk on Wednesday, organised between Manchester city council and the Ahmed Iqbal Ullah RACE Centre team.

“She [led] in the women’s sections, co-founded the Negro World newspaper, directed the Black Star Line Steamship Corporation, which is really concerned with repatriating people, funds, and resources back to the African continent.”

Listed beside them are WE Du Bois, the first African-American to earn a doctorate, and George Padmore, a Communist journalist from Trinidad. Both towering figures within the Pan-Africanist movement, Du Bois had been a key player in arranging past congresses, and Padmore had arranged the fifth.

‘It makes us feel quite close’

The next Pan-African Congress would not be held until 1974, by which time 19 of the delegates’ nations had been freed from imperial rule. Within a decade, three more would win independence.

The Manchester congress is widely credited as having tipped progress on anti-colonial efforts across Africa. The Congress was the first to endorse mass action, and the first to recognise racial injustice towards Black Brits living in the UK.

In their written Challenge to the Colonial Powers, the Congress demanded an end to colonialism; national independence and the return of land; press freedom; the right to education, trade unions, and assembly; and an end to racial discrimination in both the UK and its colonies.

It also, according to Dr Carmichael Murphy, became a new foundation for generations of activists: Kath Locke, the co-founder of Moss Side’s Abasindi Co-operative in 1980, was said to have been inspired by the movement in her efforts to create a space for Black women in the community.

“There’s lots of ways small people can be big,” Dr Carmichael Murphy said. “Kath Locke was working at one of Ras Makennon’s restaurants. She was around people like Jomo Kenyatta and George Padmore, and she wasn’t the only person in Manchester either.

“A lot of Black women’s activism throughout 70s, 80s, and 90s did really build on this Pan-Africanist approach as well. The Black Women’s Cooperative, Abyssinia Cooperative, they really had Pan-Africanism instilled in their actions.

“I wouldn’t necessarily say that the country was happy that the Congress was hosted. I think because the Congress was self funded, that made it difficult for them to stop. But what I will say is that in years afterwards Manchester has been active, and Manchester city council itself has been active in celebrating the Congress.

“I do think what’s interesting is that we’re celebrating the 80th anniversary of the Congress this year, and the plaque was installed for the 40th, and so we are as far away from the installation of the plaque as they were from the Congress itself.

“I do think that makes us feel quite close, and not that historical.”